There are a lot of different reasons to consider changing the ride height of a car. Maybe the back is too high. Maybe the front is too low. Maybe the whole car is too high or too low.

There are a lot of ways to change your vehicle’s ride height, but this article is about making relatively small changes. We’re not talking about low riders or slammed sport trucks here—instead, we’re dealing with incremental changes to fix a ride height issue.

Six of the most common ways to lower or raise a car (without torsion bars—that’s another story altogether) is via cut coils, re-arched leaf springs, coil spring spacers, lowering blocks, revised tire height (diameter), and/or dropped spindles.

All come with their own pros and cons, but actually there’s nothing wrong with any of these methods—provided the work is done right.

***

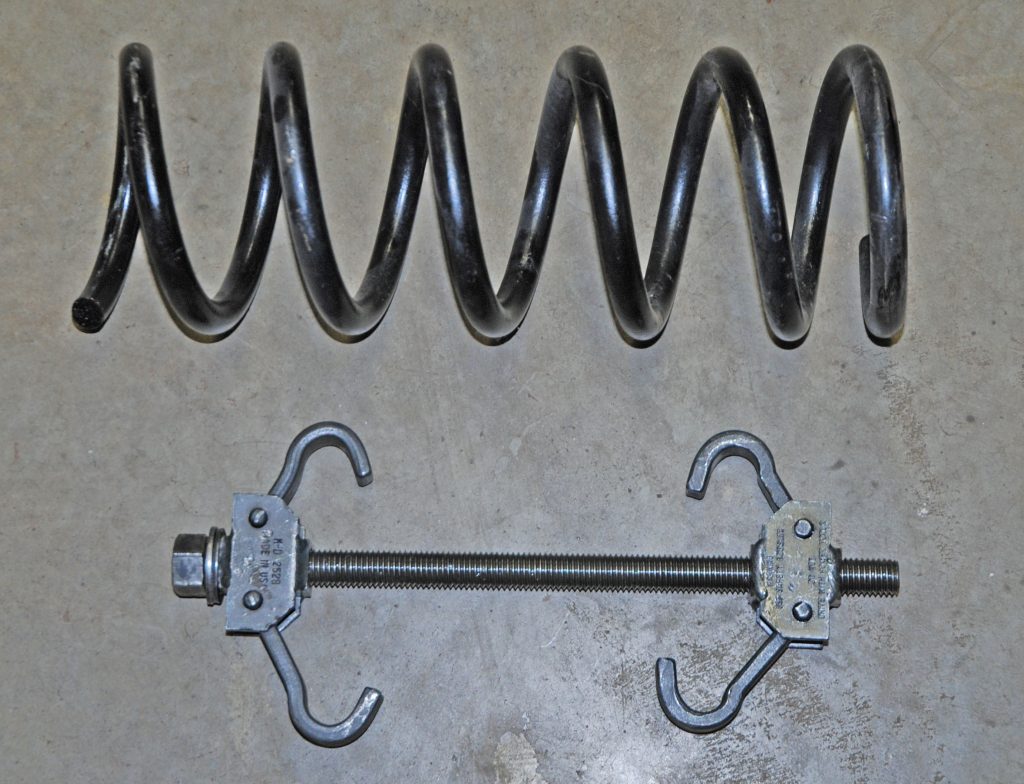

1. Cutting Coil Springs

First things first: Don’t use a torch to cut a coil (usually a half a coil is the goal), unless you really know what you’re doing! There’s a good chance you’ll destroy the spring.

If you do use an acetylene torch to cut the spring, be absolutely positive you do not quench the spring. Allow it to air cool slowly. On a similar note, don’t use a torch to droop a coil. You’re only asking for trouble. It also possible to use a cut off wheel to remove a half coil, and most likely the most common method in use.

***

2. Re-Arching Leaf Springs

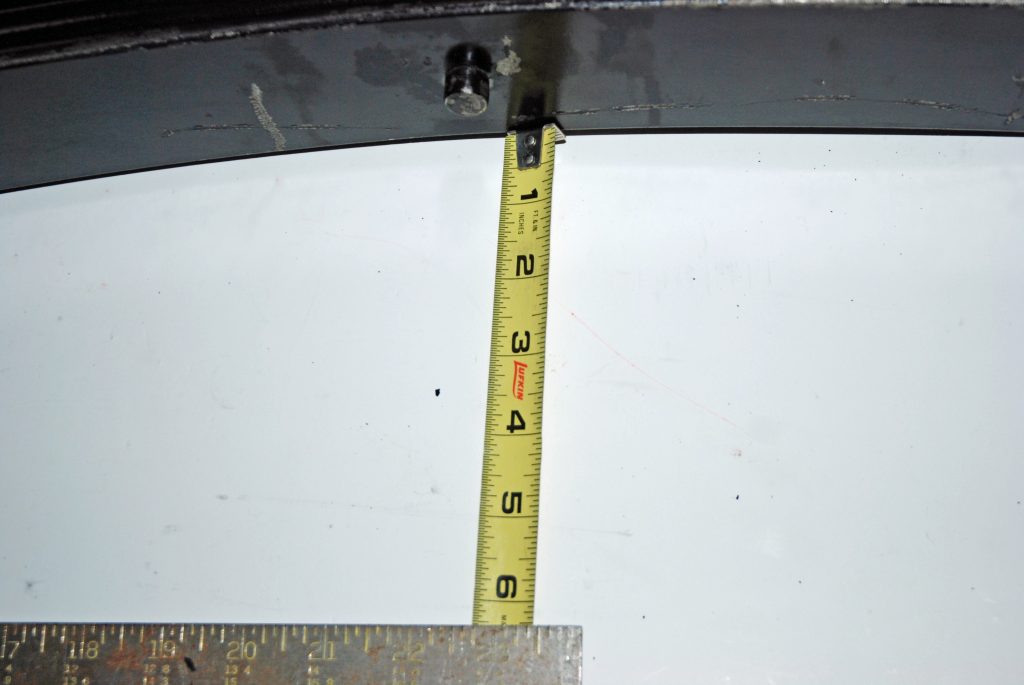

Rear leaf springs obviously can’t be cut, but it is possible to add or remove arch. Case-in-point is the leaf spring on the writer’s Nova seen in the photos. One of the new back springs had more arch than the other, when measured out of the car on the shop floor.

The fix was rather simple: I took the assembly to a local spring shop and asked them to take slightly more than a half inch out of one of the springs. It was completed in less than a day. It looked exactly the same, aside from slightly less arch. The car now sits level side to side.

***

3. Coil Spring Spacers

There are all sorts of coil spring spacers out there. The good spacers are those that fit on one end of the spring. The ones to avoid are those old ugly “adjusters” that screwed in from each side of the spring (and you won’t find those sold by Summit Racing).

Spacers are available in poly, rubber, or metal (some are actually aluminum). It might not be common knowledge, but back in the day GM used rubber spacers to adjust ride height on a large number of cars, right on the production line.

The spacers were used instead of different springs to set the ride height for different option combinations. Here’s something to consider on a front coil spring: The amount of “lift” you gain is approximately double the true thickness of the spacer.

So, for a 0.375 inch spacer, the front of the car will come up 3/4 of an inch or so. A one inch spacer raises it approximately two inches. For some applications, where the car needs to be leveled side-to-side, you can use an appropriately sized spacer in one of the coils.

***

4. Lowering Blocks

Lowering blocks for leaf springs are also perfectly acceptable. They’re even used in some NHRA Stock Eliminator cars as tuning tools (Calvert Racing manufactures blocks just for this application). There’s a wide range of lowering blocks manufactured in both aluminum and steel.

When using a lowering block, you’ll most likely need to use a set of longer U-bolts. Blocks are available individually or in kit format (with the correct length U-bolts). Some manufacturers suggest you pin the blocks to the spring perch (or if they’re steel, tack weld them).

***

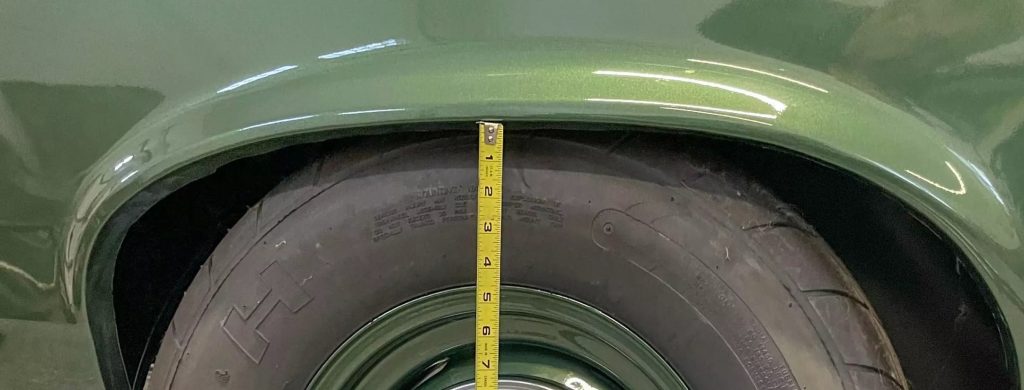

5. Tire Diameter

A ride height adjustment can be made easily if you simply swap tires. For example, the front tire on the writer’s Nova is a P205-70R15. It measures 26.3 inches tall. If I swap to a P205-75R15, the tire height goes up to 27.1 inches in diameter. On the car, that simple change raises the nose by almost half inch. Similarly, a P215-75-R15 has an overall diameter of 27.7 inches. That would make for a lift of approximately 3/4 inch. Obviously, if you reduce the diameter, then you’ll get a drop.

***

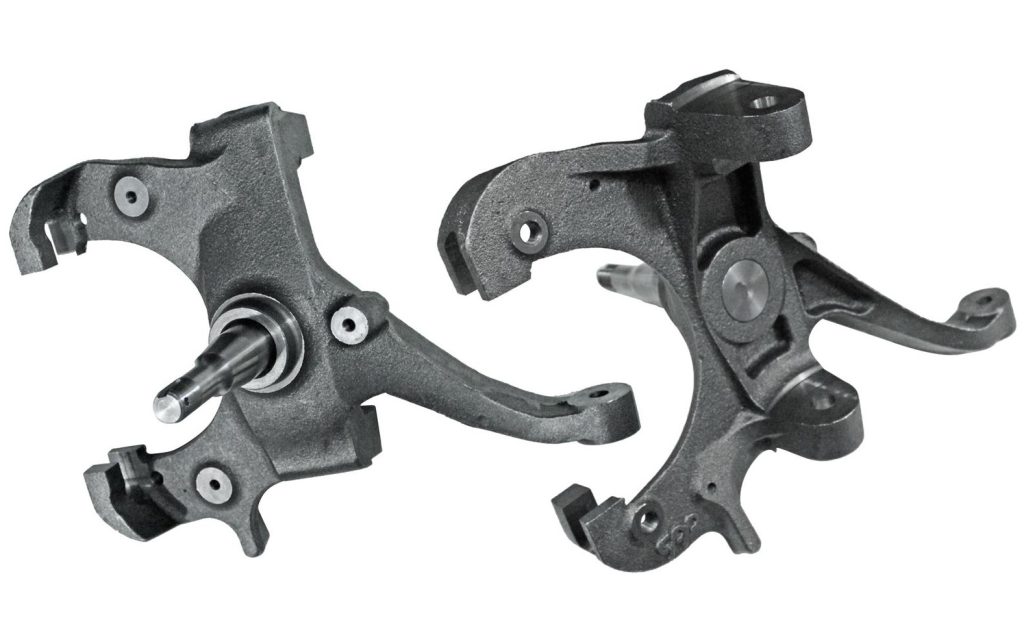

6. Dropped Spindles Or Aftermarket A-Arms

Currently, there are over 200 different dropped spindle assemblies at SummitRacing.com, covering everything from Mustangs to Tri-Five Chevys to pickup trucks. The amount of drop varies from vehicle to vehicle (application) and from manufacturer to manufacturer. The most common, however is a drop between two and 2.50 inches.

You may also appreciate this article from Jeff Smith: What’s the Best Way to Lower the Front Ride Height of a 1970 Chevy Nova?

Something you might not consider is that many aftermarket A-arm kits actually have the lower A-arm spring pocket dropped. For example, the spring pocket in the writer’s Nova (Detroit Speed A-arms) measures almost one inch lower than stock. In turn, this drops the nose of the car significantly. And Detroit Speed isn’t the only company that provides A-arms with dropped pockets. It’s best to check with the manufacturer to ensure you’re on the same page when it comes to ride height.

***

All told, there are all sorts of ways to raise or lower the nose or tail of your car. We’ve stayed away from old band-aids such as air shocks, shock extensions, and longer than stock shackles. As you can see, it’s easy enough to gain incremental changes in ride height with the pieces mentioned above.

Another informative article as usual. Thanks again Wayne.