(Image/Jeff Smith)

I have a 1969 Chevelle 396 4-speed, 3.55:1 rear ratio, F41 Chevy suspension on air shocks. When I do a burnout I have bad wheel hop. I tried letting the air out of the shocks, but it still hops. I changed all the upper and lower bushings to poly but still have wheel hop.

Will it stop if I put the QA-1 traction bars on it? I’m trying to keep the car as original looking as possible and also not throw away a lot of money. Everybody’s saying their product will stop wheel hop, but nothing so far has worked. – D.B.

…

Jeff Smith: This is a common problem with the Chevelle non-parallel, four-link coil spring rear suspension, but don’t despair—there are a couple of easy fixes.

Part of the solution is something as simple as ride height. I’ve owned Chevelles since 1971, and I have experienced this exact issue. Way back in the day, we discovered that raising the rear ride height can create some violent wheel hop.

Rear air shocks were a common addition back then, and we learned quickly that lowering the rear ride height often solved the wheel hop problem. The easiest way to establish “how low is too low?” is to look at the lower trailing arm.

A great starting place is to ensure that the lower trailing arms are parallel to the ground. When the ride height is raised, the front mounting point for the trailing arm will be higher than the rear mounting point at the rear axle housing. From your description, it’s possible that even with all the air bled from the air shocks the car still may sit too high. This may require different rear springs to lower the ride height.

Earlier ’64-’67 Chevelle rear springs employed an open wire end on the upper part of the spring that can be trimmed to lower the car. Because the rear springs on a ’69 Chevelle use a pigtail on both ends, the springs cannot be cut. Don’t try torching the springs to shorten them. This kills the spring, and is not a good way to lower a car.

You might try adding weight to the trunk, which accomplishes two things—it temporarily lowers the car’s ride height and adds weight over the rear tires, which can improve traction. If wheel hop is eliminated, then at least you will know that a lower ride height may solve the problem. This is the simplest solution.

The aftermarket offers several additional approaches that do work, though some are simpler than others. We’ll take a look at these methods and evaluate them based on how well they work. Sometimes a solution creates other problems and therefore isn’t the best approach.

Before we get into these parts, let’s look at exactly how the Chevelle rear suspension functions. A Chevelle system uses coil springs to support the vehicle weight and also employs upper and lower trailing arms. The lower trailing arms bolt to the lower portion of the frame and connect underneath the rear axle. The upper arms are connected to a crossmember in the upper part of the frame and connect to the top portion of the axle housing. The upper arms also are splayed at an outward angle from the top. This forms a simple triangle that eliminates the need for a Watts Link or Panhard bar to laterally locate the housing under the car.

When power is applied to the rear axle, the pinion gear tries to climb the ring gear, creating multiple forces. First, the axle housing (as viewed from the rear of the car) attempts to spin counter-clockwise, lifting the right rear tire and forcing the left rear tire into the pavement. This is why non-positraction equipped cars always spin the right rear tire.

If we view the rear axle assembly from the passenger side of the car, when torque is applied the pinion also attempts to climb the ring gear, which then attempts to rotate the pinion upward. The upper control arms immediately go into tension (pulled apart), while the lower control arms are placed in compression. The control arms prevent the axle housing from moving, sending the power through the axles to the rear tires.

This is where the rear suspension action gets a little complicated. Let’s start by drawing an imaginary line from the lower rear mounting point of the lower control arm to the front control arm mounting point and extending that line forward. Next, extend another similar line through the upper control arm mounting points. Ideally, the extended upper and lower lines will intersect at some point within the wheelbase of the car. The intersection point is called the instant center for the rear suspension. We won’t get into all the details around this, as it is a complex issue.

Sometimes the upper and lower lines are parallel and don’t intersect. This can cause the rear suspension to squat on acceleration. You can think of these extended lines like an enormously long lever working on the rear suspension. You can shorten this imaginary lever either by raising the upper rear locating point on the rear axle or lowering the rear lower mounting point.

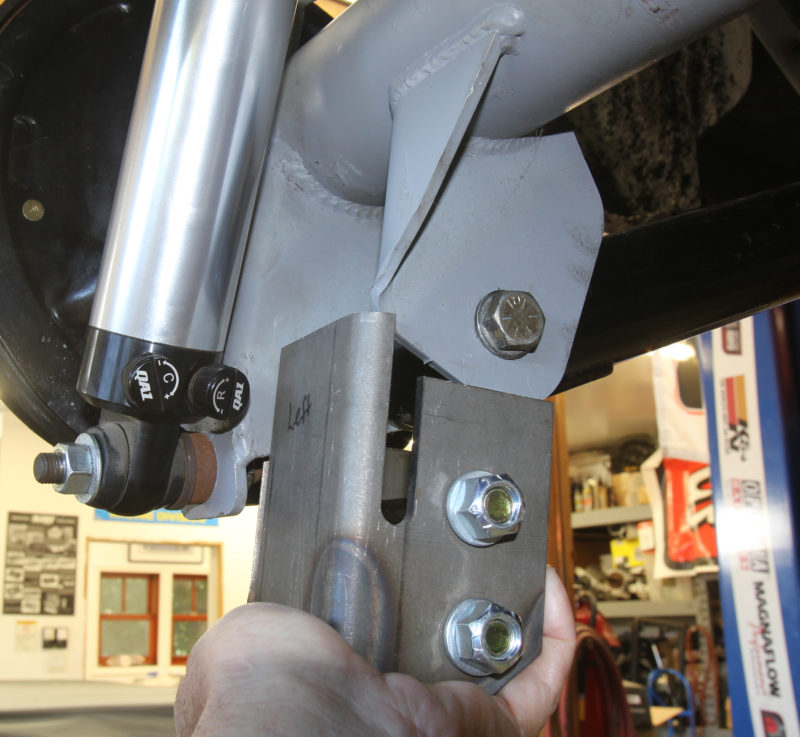

You mentioned a QA1 traction kit. QA1 does sell an anti-hop bar (#5213) that will raise the upper control arm mounting point and improve traction. The limitation for this device is that since it raises the upper mounting point, it reduces the clearance to the floor pan. In some instances, this can cause contact between the mount and the floor, requiring a raised rear ride height.

The second way to accomplish the lever arm trick is to lower the rear lower control arm mounting point on the axle housing. Global West makes a bracket for the 12-bolt that welds to the housing and lowers the rear mounting point. This does place the lower trailing arm at a slight upward angle, but with a lower ride height it improves traction and effectively eliminates body squat on acceleration. One important note is to never employ both the upper and lower control arm conversions at the same time—use one or the other but never both.

This is Global West’s anti-squat bracket. The bracket fits inside the stock lower control arm bracket and the upper bolt in the bracket bolts through the stock location. Then the lower bolt repositions the lower control arm. This bracket must be welded in place. (Image/Jeff Smith)

You also asked about changing the shocks. Air shocks are generally not considered ideal for performance applications. Single or double-adjustable shocks form QA1, Viking, or dozens of other companies can offer tuning changes for ride quality and also improve traction. However, an adjustable shock will not override a poor rear suspension configuration.

Hopefully this will help you dial in your Chevelle. Most often, you can eliminate that wheel hop just by lowering the car enough to make the lower control arm parallel with the ground.

Adjustable control arms on top to get Pinon angle correct and then just box in lowers most are u shape then get ride height set tire pressure is key on track our 69 ss full body n/a 350 7.47 and 1.9 60ft on street tires 1/8 mile no nos

Great information, thank you. I put 120 pounds in my trunk over the axle. It lowered the car a quarter inch. Is it the quarter inch or the weight that stopped the wheel hop? I still get s little wheel hop at the end of the burnout, more weight?

Tom

Probably a combination of the two but the weight also lowered the car more than the quarter-inch you mentioned. With a rear spring rate of around 150 lbs/inch, a 120 pounds would lower the car almost an inch. Lower the rear ride height so that the lower control arms are parallel with the ground and it will work even better.

120 pounds divided by two 150 inch pound springs, in theory, won’t quite compress the two springs much over 1/3 of an inch each.

Jeff l measured it before the weight was added and after. When l got the car he had changed the springs and put boxed lower control arms had to cut the springs ,lowered the car one and a half inches already. Since adding the weight the handling has improved a lot not squirrelly anymore. How can l lower the lower control arm.? Btw the rear is half inch higher than the front

Easiest way to make the lower control arm level is to lower the ride height of the car. This will lower the front mounting position as the ride height comes down. As pointed out in the story, you can radically change the instant center with the Global West bracket, but see what effect you can manage by just lowering the car to get the lowe rcontrol arm parallel with the ground. That will help traction and should eliminate the wheel hop.Lowering the front of the car will also help.

Back in the day a lot of us used Air Bags in the coil springs. They served 2 purposes: Raised the rear just enough for the slicks we were running and second allowed us to pre-load the Rt rear. Never had any wheel hop. Usually, the top limit on air pressure was 20 lbs. More than that could blow the Air Bag… ask me how I know. Just an old school fix from about 50 yrs. ago. Doubt if the “Air-Lift” bags can be sourced these days.

Hey Guys, I’m really confused! I have two 69 Chevelles both with big blocks, both stock. One has no wheel hop at all, the other has really bad wheel hop.

I replaced the rear springs, new KYB shocks, new boxed lower control arms and I even installed a a set of Air Lift 1000 airbags. Nothing has helped, both cars sit at a stock height. I really don’t want to lower this car, I don’t like the look, my other car sits at stock height and has no problem.

Any ideas?

Use no hop bars

and adjustable arms for the upper, adjust pinion angle 1-2 degrees down.

Soft or loose bushings in the car that wheel hops. If the car is “stock” then there shouldn’t be any problem with the driveline angle, but the car is 50 years old and may not be as “stock” as you think. Set you trans main shaft centerline and pinion gear main shaft centerline to equal parallel angles with the center of earth’s gravity and then set your ride height to achieve a 0 degree u-joint operating angle on both u-joints.

I have a 2018 AWD Mercedes e63s AWD. 750whp/730tq. Ran a 10.51 in 70 degree weather. Record on model is a 10.436 so trying to break record. I changed tires from Michelin pilot 4S 265 front/295 back, to SC2’s 265 front/305 back.

Went to track when temp dropped to 60/lots of vht on the track. launched it, wheel hopped, broke the transmission.

Never had wheel hop issue prior to tire the change. Been researching on internet/trying to figure out what to do.

1. Return stickier wider SC2’s and stay with the 4S’s.

2. Reduce air pressure in front and raise in the back,

use stiffer suspension/minimize weight shift to back.

I’d like to hear from an expert to get recommendation.

Happy Thanksgiving to all.