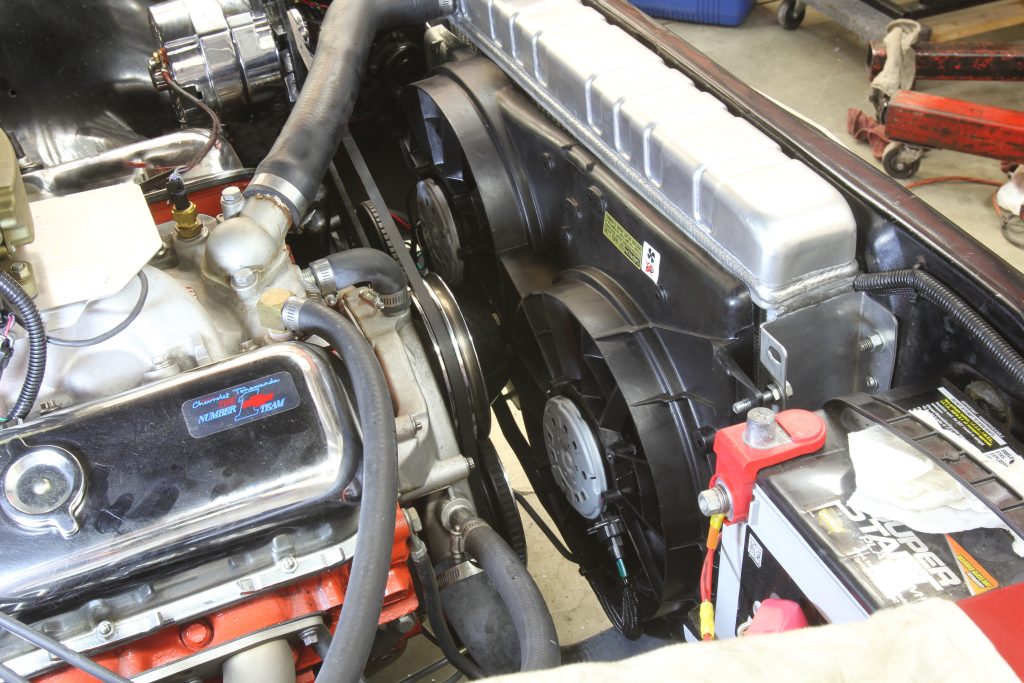

I’m trying to help out a friend with a ‘66 Chevelle project. It has a big block with a six speed in it. I think it was a small block car originally. They bought a DeWitts aluminum radiator with a single electric fan setup. I went to install it and there was not enough room between the core support and water pump. It has an aftermarket accessory drive. I started looking a little closer at the engine and noticed they had dented the headers to clear the driver’s side of the cross member. It also seems to have more clearance for the HEI than I expected.

Any suggestions? Thanks,

D.L.

This is not an unusual situation. Early big block Chevelles are famous for positioning the engine far forward in the chassis, which makes positioning electric fans and big radiators somewhat of a challenge.

The first important point that you made is that you are using a large, single electric fan. Unfortunately, the position of a large single fan’s electric motor places it almost directly in line with the centerline of the water pump. Generally, the water pump snout is the farthest positioned component in the accessory drive. This makes it difficult to use a large single fan, especially if the fan is a high output version with a large electric motor. These tend to employ a thicker electric motor that positions it farther rearward—and directly in the path of the water pump snout.

A friend of ours was faced with this same dilemma several years ago with a big block 1966 Chevy El Camino. His solution was to use a pair of smaller electric fans that positioned their electric motors away from the water pump which would allow him to use a large aluminum radiator along with a pair of fans that he could control separately. He also was using a DeWitts aluminum radiator.

Several companies offer high quality electric fans with dual fans being the way to go. Further research revealed a very affordable dual fan assembly originally intended as an OEM replacement fan package for the 1996-2000 Ford Contour. This dual fan assembly is interesting because each of the twin fans operate together both in low and high speeds. The advantage to this is that with either a vertical or horizontal flow radiator if only one fan was operating only half the radiator would benefit from the fan operation. With this Contour fan package, both fans operate at both low and high speeds with the high speed used only if temperatures exceed a given level.

We also tested these fan motors for amperage draw since if they pull high amperage, they may overwhelm the charging system which would require a larger alternator and additional cost. To our surprise, both fans at low speed pull only about 10 amps and at high speed only about 15 amps. This is well within the ability of most decent alternators. Of course, if at idle this amperage draw is too much for your current alternator, then a much higher output alternator will be required.

It’s worth noting that you have to be a discerning buyer when looking at alternator output claims. As an example, Powermaster will offer an output number for both at idle and higher engine speeds. Keep in mind that all alternators are rated for output in amps when tested at ambient or cold conditions. Once the alternator is up to full operating temperature (which can happen very quickly), the added heat reduces the output by as much as 15 to 20 percent.

So if your alternator is rated to produce 100 amps at idle—it really is only capable of generating roughly between 80 and 85 amps once it is up to normal operating temperature. Keep that in mind when considering purchasing a high output alternator.

These Contour fans will not directly bolt up to the DeWitts radiator but we were able to adapt the fans by using the built-in fan body to drill mounting holes in the DeWitts radiator flanges by using spacers and 5/16 inch bolts.

You did not mention if this big block will be controlled with electronic fuel injection. If so, the fan controls are easy. But it’s not that much more difficult to control the fans with two separate temperature trigger sensors. For example, you can use a pair of Summit Racing temperature sensing switches. (We’ve listed the part numbers at the bottom of this post, but one comes on at 185 degrees and turns off when the temperature drops to 175 degrees.) This switch would control the low-speed fans while the second would control the high speed fans to switch on if the coolant temperature achieves 200 degrees or higher.

These switches operate by completing the ground circuit and are best employed by using a relay. When using the relay, power will come directly from the battery (through a fused connection of course) and is routed by the relay to the electric fan 12 volt power connection. Switched 12 volt power will come from a power source that is controlled by the ignition switch. Finally, the ground connection is supplied by the temperature sensor.

These fans generally do not pull more than 30 amps during startup, so an individual relay should be sufficient for the low speed and a separate one for the high speed side of the fans. Of course, you could also include an override switch from the ground side of the relay to operate the fans manually if necessary or with the ignition switch off.

This should offer you a reasonable approach to finding a set of electric fans that will not only cool your engine on hot summer days but also fit within the tight confines of your big block engine compartment.

Chevelle Dual Electric Fan Conversion Parts List

- DeWitts aluminum radiator, DWR-1139002M

- Four Seasons twin electric fan, FSS-75282

- Bosch 30-amp electric relay, BCH-0332209150

- Four Seasons relay connectors, FSS-37211

- Summit Electric fan temp. switch, 185-on, SUM-890117

- Summit Electric fan temp. switch, 200-on, SUM-890018

- Summit Electric fan relay kit, switch, 185-on, SUM-890115

Hey Jeff,

I’m installing this setup in my Camaro after reading this article. Do you have a wiring diagram for it?

Thanks,

Terrill